Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Opening the torrent file

- Getting peers via the tracker

- Downloading from peers

- Conclusion

1. Introduction

1.1 About this guide

This guide will build a simple bittorrent client from scratch in node.js. By the end of this tutorial you should be able to use the command line to download the shared contents of a torrent file.

I had two audiences in mind for this guide. First is anyone who has learned the basics of javascript and looking for an intermediate level tutorial. Second is for web developers who may already have a good grasp of javascript but little experience working on the backend. This guide will go over things like reading/writing to file and network sockets.

I’ll be committing changes on this project using git, so you’ll be able to see how the project evolves step by step. You can find the project’s github page here. The first commit will just be a bare package.json, .gitignore file, and a sample torrent file for you to work with. I’ll also mark points throughout this guide with links to commits.

1.2 Overview of bittorrent

The bittorrent protocol has to two main parts.

Step 1: You need to send a request to something called a tracker, and the tracker will respond with a list of peers. More specifically, you tell the tracker which files you’re trying to download, and the tracker gives you the ip address of the users you download them from. Making a request to a tracker also adds your ip address to the list of users that can share that file.

Step 2: After you have the list of peer addresses, you want to connect to them directly and start downloading. This happens through an exchange of messages where they tell you what pieces they have, and you tell them which pieces you want.

You can get an idea of how this all works in the image below (credit to morehawes.co.uk):

1.3 Links and references

These are links that I referenced many times during this project:

wiki.theory.org/index.php/BitTorrentSpecification - This is an unofficial bittorrent specification but basically has everything you need to know. Detailed and very readable.

www.bittorrent.org/beps/bep_0015.html - The only thing thing you won’t find in the unofficial spec is how to form a request to a tracker that uses a UDP url. But you can find it here in this link. I’ll remind you about this link again when I cover trackers and UDP.

www.morehawes.co.uk/the-bittorrent-protocol - A very good high level explanation of the bittorrent protocol. With pictures!

www.kristenwidman.com/blog/33/how-to-write-a-bittorrent-client-part-1 - Another good high level explanation.

www.bittorrent.org/beps/bep_0020.html - BEP for peer id conventions.

2. Opening the torrent file

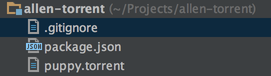

*Github commit #1: initial commit

Enough intro, let’s get started on the code! If you click the link above to go to our initial commit, you see that we’re basically starting from a blank slate. This is our current file structure:

You can see that I’ve added a torrent for us to work with. It contains a picture of a puppy in a cup. Let’s create a new file called index.js and start by opening the torrent file.

index.js:

'use strict';

const fs = require('fs');

const torrent = fs.readFileSync('puppy.torrent');

console.log(torrent.toString('utf8'));readFileSync is the easiest way to read the contents of a file. But if you

run this code you’ll realize that readFileSync returns a buffer

, not a string. Later on you’ll see that all our network messages are sent

and received in the form of buffers, so it’s important that you have a good

understanding of how they work. If you’re not familiar with buffers in node.js

I’ve written a mini guide on buffers here. The short story is that buffers

represent a sequence of raw bytes. If you want to read the buffer as a string

you have to specify an encoding scheme (you can see I used utf-8 above).

The output should have looked something like this:

'd8:announce43:udp://tracker.coppersurfer.tk:6969/announce10:created by13:uTorrent/187013:creation datei1462355939e8:encoding5:UTF-84:infod6:lengthi124234e4:name9:puppy.jpg12:piece lengthi16384e6:pieces160:T�k�/�_(�S\u0011h%���+]q\'B\u0018�٠:����p"�j����1-g"\u0018�s(\u001b\u000f���V��=�h�m\u0017a�nF�2���N\r�ǩ�_�\u001e"2���\'�wO���-;\u0004ע\u0017�ؑ��L&����0\u001f�D_9��\t\\��O�h,n\u001a5g�(��仑,�\\߰�%��U��\u0019��C\u0007>��df��ee'

2.1 Bencode

*Github commit #2: open torrent, get tracker url

That output probably looked fairly incomprehensible to you, and that’s because you’ve probably never heard of bencode. Bencode is data serialization format, and I don’t think I’ve seen it used anywhere outside of torrent files. But you may be familiar with JSON or XML, and bencode is essentially the same idea, it just uses a slightly different format.

Here’s the same data again in JSON:

'{"announce":"udp://tracker.coppersurfer.tk:6969/announce","created by":"uTorrent/1870","creation date":1462355939,"encoding":"UTF-8","info":{"length":124234,"name":"puppy.jpg","piece length":16384,"pieces":"T�k�/�_(�S\\u0011h%���+]q\'B\\u0018�٠:����p\\"�j����1-g\\"\\u0018�s(\\u001b\\u000f���V��=�h�m\\u0017a�nF�2���N\\r�ǩ�_�\\u001e\\"2���\'�wO���-;\\u0004ע\\u0017�ؑ��L&����0\\u001f�D_9��\\t\\\\��O�h,n\\u001a5g�(��仑,�\\\\߰�%��U��\\u0019��C\\u0007>��df��"}}'

That should look a bit more familiar (except for the pieces property, which I’ll get to later). While it’s possible to write our own bencode parser, there are many good open source libraries that can do it for us. I just googled “bencode node” and installed the first result:

npm install --save bencode

Now we can parse our torrent into data that we can interact with:

'use strict';

const fs = require('fs');

const bencode = require('bencode');

const torrent = bencode.decode(fs.readFileSync('puppy.torrent'));

console.log(torrent.announce.toString('utf8'));You’ll notice that many of the values in our decoded torrent object are

buffers. It’s possible to convert all buffers to strings by passing ‘utf8’ (or

any other encoding scheme) as the second arguemnt to bencode.decode, but

since we’ll be working mostly with buffers when we use this data in the

networking portion of this project, it’s best to keep them as buffers.

3. Getting peers via the tracker

In the code above I console.log the announce property of the torrent. For

this particular file it happens to be udp://tracker.coppersurfer.tk:6969/announce.

The announce url is what I’ve been calling the tracker’s url, it is the

location of the torrent’s tracker.

One interesting thing you’ll notice is that instead of the usual ‘http’ in front, this url has ‘udp’. This is because instead of the http protocol, you must use the udp protocol. It used to be that all trackers used http, but nowadays nearly all new torrents are using udp. So what’s the difference between the two protocols, and why switch to udp?

3.1 Http vs udp vs tcp

The main reason that most trackers now use udp is that udp has better performance than http. Http is built on top of another protocol called tcp, which we’ll use later in the project when we start actually downloading files from peers. So what’s the difference between tcp and udp?

The main difference is that tcp guarantees that when a user sends data, the other user will recieve that data in its entirety, uncorrupted, and in the correct order – but it must create a persistent connection between users before sending data and this can make tcp much slower than udp. In the case of upd, if the data being sent is small enough (less than 512 bytes) you don’t have to worry about receiving only part of the data or receiving data out of order. However, as we’ll see shortly, it’s possible that data sent will never reach its destination, and so you sometimes end up having to resend or re-request data.

For these reasons, udp is often a good choice for trackers because they send small messages, and we use tcp for when we actually transfer files between peers because those files tend to be larger and must arrive intact.

3.2 Sending messages with UDP

In the code below, I’ve made some changes to show how we can send and receive messages via UDP. NOTE: This example may not get a response back because the message being sent isn’t formatted correctly. This is just an example to show the various modules we’ll be using.

'use strict';

const fs = require('fs');

const bencode = require('bencode');

// 1

const dgram = require('dgram');

const Buffer = require('buffer').Buffer;

const urlParse = require('url').parse;

const torrent = bencode.decode(fs.readFileSync('puppy.torrent'));

// 2

const url = urlParse(torrent.announce.toString('utf8'));

// 3

const socket = dgram.createSocket('udp4');

// 4

const myMsg = Buffer.from('hello?', 'utf8');

// 5

socket.send(myMsg, 0, myMsg.length, url.port, url.host, () => {});

// 6

socket.on('message', msg => {

console.log('message is', msg);

});There’s a lot going on in this code so let’s try to break it down.

-

First we require 3 more modules,

dgram,buffer, andurl. These are all just from the standard library. -

I use the

urlmodule’s parse method on our tracker url. This lets me easily extract different parts of the url like its protocol, hostname, port, etc. -

The

dgrammodule is our module for udp, and here I’m creating a new socket instance. A socket is an object through which network communication can happen. We pass the argument ‘udp4’, which means we want to use the normal 4-byte IPv4 address format (e.g. 127.0.0.1). You can also pass ‘udp6’ for the newer IPv6 address format (e.g. FE80:CD00:0000:0CDE:1257:0000:211E:729C) but this format is still rarely used. -

In order to send a message through a socket, it must be in the form of a buffer, not a string or number.

Buffer.fromis an easy way to create a buffer from a string, see my mini guide for more info on buffers. -

The socket’s

sendmethod is used for sending messages. The first argument is the message as a buffer. The next two arguments let you send just part of the buffer as the message by specifying an offset and length of the buffer, but if you’re just sending the whole buffer you can just set the offset to 0 and the length to the whole length of the buffer. Next is the port and host of the receiver’s url. Finally the last argument is a callback for when the message has finished sending. -

Here we tell the socket how to handle incoming messages. Whenever a message comes back through the socket it will be passed to the callback function.

3.3 UDP tracker protocol and message format

Now we know how to send and receive messages through UDP, but in order to get a list of peers from the tracker, the tracker will be expecting messages to follow a specific protocol. In short you must:

- Send a connect request

- Get the connect response and extract the connection id

- Use the connection id to send an announce request - this is where we tell the tracker which files we’re interested in

- Get the announce response and extract the peers list

Since the amount of code related to the tracker is starting to get large, at this point I want to create a new file called tracker.js and move all tracker related code there.

tracker.js:

'use strict';

const dgram = require('dgram');

const Buffer = require('buffer').Buffer;

const urlParse = require('url').parse;

module.exports.getPeers = (torrent, callback) => {

const socket = dgram.createSocket('udp4');

const url = torrent.announce.toString('utf8');

// 1. send connect request

udpSend(socket, buildConnReq(), url);

socket.on('message', response => {

if (respType(response) === 'connect') {

// 2. receive and parse connect response

const connResp = parseConnResp(response);

// 3. send announce request

const announceReq = buildAnnounceReq(connResp.connectionId);

udpSend(socket, announceReq, url);

} else if (respType(response) === 'announce') {

// 4. parse announce response

const announceResp = parseAnnounceResp(response);

// 5. pass peers to callback

callback(announceResp.peers);

}

});

};

function udpSend(socket, message, rawUrl, callback=()=>{}) {

const url = urlParse(rawUrl);

socket.send(message, 0, message.length, url.port, url.host, callback);

}

function respType(resp) {

// ...

}

function buildConnReq() {

// ...

}

function parseConnResp(resp) {

// ...

}

function buildAnnounceReq(connId) {

// ...

}

function parseAnnounceResp(resp) {

// ...

}*Github commit #3: move UDP code into new file tracker.js

Here I’m exporting just the one function getPeers which fairly closely follow

the 4 step protocol that I listed above. When we finally get the list of peers

we pass it to the callback. The other 6 functions are as

follows:

-

udpSendis just a convenience function that mostly just callssocket.sendbut lets me avoid having to set the offset and length arguments since I know I want to send the whole buffer, and sets a default callback which is just an empty function, since I mostly don’t need to do anything after sending the message (see point 5 in the previous section if you need a refresher onsocket.send) -

respTypewill check if the response was for the connect or the announce request. Since both responses come through the same socket, we want a way to distinguish them. -

to 6. These 4 methods will build and parse the connect and announce messages.

index.js has also been refactored to use our new getPeers function.

index.js:

'use strict';

const fs = require('fs');

const bencode = require('bencode');

const tracker = require('./tracker');

const torrent = bencode.decode(fs.readFileSync('puppy.torrent'));

tracker.getPeers(torrent, peers => {

console.log('list of peers: ', peers);

});3.3.1 Connect messaging

Now let’s take a look at actually building the messages. Each message is a buffer with a specific format described in the BEP. Let’s take a look at the connect request first.

The BEP describes the connect request as follows:

Offset Size Name Value

0 64-bit integer connection_id 0x41727101980

8 32-bit integer action 0 // connect

12 32-bit integer transaction_id ? // random

16

This tells us that our message should start out with a 64-bit (i.e. 8 bytes) integer at index 0, and that the value should be 0x41727101980. Since we just write 8 bytes, the index of the next part is 8. Now we write 32-bit integer (4 bytes) with the value 0. This moves us up to an offset of 12 bytes, and we write a random 32-bit integer. So the total message length is 8 bytes + 4 bytes + 4bytes = 16 bytes long, and should look something like this:

<Buffer 00 00 04 17 27 10 19 80 00 00 00 00 a6 ec 6b 7d>

Let’s see how we can implement this in our tracker.js file.

tracker.js:

// rest of file has been left out to save space

const crypto = require('crypto'); // 1

function buildConnReq() {

const buf = Buffer.alloc(16); // 2

// connection id

buf.writeUInt32BE(0x417, 0); // 3

buf.writeUInt32BE(0x27101980, 4);

// action

buf.writeUInt32BE(0, 8); // 4

// transaction id

crypto.randomBytes(4).copy(buf, 12); // 5

return buf;

}-

First we require the built-in crypto module to help us create a random number for our buffer. We’ll see that in action shortly.

-

Then we create a new empty buffer with a size of 16 bytes since we already know that the entire message should be 16 bytes long.

-

Here we write the the connection id, which should always be 0x41727101980 when writing the connection request. We use the method

writeUInt32BEwhich writes an unsigned 32-bit integer in big-endian format (more info here). We pass the number 0x417 and an offset value of 0. And then again the number 0x27101980 at an offset of 4 bytes.You might be wondering 2 things: what’s with the 0x? and why do we have to split the number into two writes?

The 0x indicates that the number is a hexadecimal number, which can be a more conventient representation when working with bytes. Otherwise they’re basically the same as base 10 numbers.

The reason we have to write in 4 byte chunks, is that there is no method to write a 64 bit integer. Actually node.js doesn’t support precise 64-bit integers. But as you can see it’s easy to write a 64-bit hexadecimal number as a combination of two 32-bit hexadecimal numbers.

-

Next we write 0 for the action into the next 4 bytes, setting the offset at 8 bytes since just wrote an 8 byte integer. This values should always be 0 for the connection request.

-

For the final 4 bytes we generate a random 4-byte buffer using

crypto.randomByteswhich is a pretty handy way of creating a random 32-bit integer. To copy that buffer into our original buffer we use thecopymethod passing in the offset we would like to start writing at.

Parsing the response is much simpler. Here’s how the response is formatted:

Offset Size Name Value

0 32-bit integer action 0 // connect

4 32-bit integer transaction_id

8 64-bit integer connection_id

16

And here’s the parsing function:

tracker.js:

// rest of file has been left out to save space

function parseConnResp(resp) {

return {

action: resp.readUInt32BE(0),

transactionId: resp.readUInt32BE(4),

connectionId: resp.slice(8)

}

}You can see I read the action and the transaction id as unsigned 32 bit

big-endian integers, passing in the offset. Then I just use the

slice

method to get the last 8 bytes. Since I can’t read a 64-bit integer it’s easier to

just leave it as a buffer.

github commit #4: add connection request and response functions

3.3.2 Announce messaging

Many of the concepts here are the same as the connect request and response. However there are some things to look out for that I’ll mention. Here’s the announce request below.

Offset Size Name Value

0 64-bit integer connection_id

8 32-bit integer action 1 // announce

12 32-bit integer transaction_id

16 20-byte string info_hash

36 20-byte string peer_id

56 64-bit integer downloaded

64 64-bit integer left

72 64-bit integer uploaded

80 32-bit integer event 0 // 0: none; 1: completed; 2: started; 3: stopped

84 32-bit integer IP address 0 // default

88 32-bit integer key ? // random

92 32-bit integer num_want -1 // default

96 16-bit integer port ? // should be betwee

98

tracker.js

// rest of file has been left out to save space

// see notes below about what this is

const torrentParser = require('./torrent-parser');

const util = require('./util');

module.exports.getPeers = (torrent, callback) => {

// ...

// this line now gets passed the torrent

const announceReq = buildAnnounceReq(connResp.connectionId, torrent);

// ...

};

function buildAnnounceReq(connId, torrent, port=6881) {

const buf = Buffer.allocUnsafe(98);

// connection id

connId.copy(buf, 0);

// action

buf.writeUInt32BE(1, 8);

// transaction id

crypto.randomBytes(4).copy(buf, 12);

// info hash

torrentParser.infoHash(torrent).copy(buf, 16);

// peerId

util.genId().copy(buf, 36);

// downloaded

Buffer.alloc(8).copy(buf, 56);

// left

torrentParser.size(torrent).copy(buf, 64);

// uploaded

Buffer.alloc(8).copy(buf, 72);

// event

buf.writeUInt32BE(0, 80);

// ip address

buf.writeUInt32BE(0, 80);

// key

crypto.randomBytes(4).copy(buf, 88);

// num want

buf.writeInt32BE(-1, 92);

// port

buf.writeUInt16BE(port, 96);

return buf;

}util.js:

'use strict';

const crypto = require('crypto');

let id = null;

module.exports.genId = () => {

if (!id) {

id = crypto.randomBytes(20);

Buffer.from('-AT0001-').copy(id, 0);

}

return id;

};Here’s a quick list of things I want to mention about this code:

-

“peer id” is used to uniquely identify your client. I created a new file called util.js to generate an id for me. A peer id can basically be any random 20-byte string but most clients follow a convention detailed here. Basically “AT” is the name of my client (allen-torrent), and 0001 is the version number.

As you can see the id is only generated once. Normally an id is set every time the client loads and should be the same until it’s closed. We’ll we using the id again later.

-

The code for calculating “info hash” and “left” are a bit complicated so I wanted to split that out into a new file called torrent-parser.js. We’ll go over that in the next section, but for now you can just ignore those parts.

-

Notice that this function takes a

torrentparameter now. Again, this is for the “info hash” and “left” fields, we’ll be going over that shortly. -

If you look at the BEP for this request it tells you what the offsets should be, you don’t have to count them out yourself!

-

I expect

connIdto be a buffer, since that’s how we left it in theparseConnRespmethod, so I just copy it into the buffer directly. -

There are a couple spots where I need a 64-bit integer but since they’re always initialized to 0, I just used

Buffer.alloc(8), as this will just create an 8-byte buffer with all 0s. -

For the “num want” part I want to point out that I used writeInt32BE instead of writeUIntBE (note the U). Because the number is negative you cannot used the unsigned version.

-

Finally, for the port, the official spec says that the ports for bittorrent should be between 6881 and 6889, so I’ve decided to use a default of 6681.

Now let’s take a look at parsing the response:

Offset Size Name Value

0 32-bit integer action 1 // announce

4 32-bit integer transaction_id

8 32-bit integer interval

12 32-bit integer leechers

16 32-bit integer seeders

20 + 6 * n 32-bit integer IP address

24 + 6 * n 16-bit integer TCP port

20 + 6 * N

It’s a bit tricky because the number of addresses that come back isn’t fixed. The addresses come in groups of 6 bytes, the first 4 represent the IP address and the next 2 represent the port. So our code will need to correctly break up the addresses part of the response.

// rest of file has been left out to save space

function parseAnnounceResp(resp) {

function group(iterable, groupSize) {

let groups = [];

for (let i = 0; i < iterable.length; i += groupSize) {

groups.push(iterable.slice(i, i + groupSize));

}

return groups;

}

return {

action: resp.readUInt32BE(0),

transactionId: resp.readUInt32BE(4),

leechers: resp.readUInt32BE(8),

seeders: resp.readUInt32BE(12),

peers: group(resp.slice(20), 6).map(address => {

return {

ip: address.slice(0, 4).join('.'),

port: address.readUInt16BE(4)

}

})

}

}Most of this code is pretty straightforward. I think you could put the group

function outside or in a new file which would make it reusable, but for the

purposes of this tutorial I think it’s fine. Also a bit surprising that you can

call join on a buffer. This is a bit fancy as it coerces the bytes into a

string but seems to work and I think it looks nice.

3.3.3 Info hash and torrent size

I created a new file called torrent-parser.js where I can keep all the code related getting information out of a torrent file. This means I also want to move the code for opening a torrent file here.

torrent-parser.js:

'use strict';

const fs = require('fs');

const bencode = require('bencode');

module.exports.open = (filepath) => {

return bencode.decode(fs.readFileSync(filepath));

};

module.exports.size = torrent => {

// ...

};

module.exports.infoHash = torrent => {

// ...

};index.js:

'use strict';

const fs = require('fs');

const bencode = require('bencode');

const tracker = require('./tracker');

const torrentParser = require('./torrent-parser');

const torrent = torrentParser.open('puppy.torrent');

tracker.getPeers(torrent, peers => {

console.log('list of peers: ', peers);

});github commit #5: add announce request and response

3.3.3.1 Info Hash

Now let’s go back to when we first opened the torrent file. Remember it looked something like this:

'{"announce":"udp://tracker.coppersurfer.tk:6969/announce","created by":"uTorrent/1870","creation date":1462355939,"encoding":"UTF-8","info":{"length":124234,"name":"puppy.jpg","piece length":16384,"pieces":"T�k�/�_(�S\\u0011h%���+]q\'B\\u0018�٠:����p\\"�j���1-g\\"\\u0018�s(\\u001b\\u000f���V��=�h�m\\u0017a�nF�2���N\\r�ǩ�_�\\u001e\\"2���\'�wO���-;\\u0004ע\\u0017�ؑ��L&����0\\u001f�D_9��\\t\\\\��O�h,n\\u001a5g�(��仑,�\\\\߰�%��U��\\u0019��C\\u0007>��df��"}}'

Last time we pulled the announce property from this object. Can you see that it also has an info property? If you were take the info property and pass it through a SHA1 hashing function, you would get the info hash! You can apply a SHA1 hash easily using the built-in crypto module.

torrent-parser.js:

// rest of file has been left out to save space

const bencode = require('bencode');

const crypto = require('crypto');

module.exports.infoHash = torrent => {

const info = bencode.encode(torrent.info);

return crypto.createHash('sha1').update(info).digest();

};Why use a SHA1 hashing function?

SHA1 is one of many hashing functions but it’s the one used by bittorrent so

in our case no other hashing function will do. We want to use a hash because

it’s a compact way to uniqely identify the torrent. A hashing function returns

a fixed length buffer (in this case 20-bytes long). For example, our example

torrent would output <Buffer 11 7e 3a 66 65 e8 ff 1b 15 7e 5e c3 78 23 57 8a db 8a 71 2b>.

Because it’s very unlikely for two inputs to output the same hash value, and because the input (the info property) contains information about every piece of the torrent’s files (more about this later), it’s a good way to uniquely identify a torrent. That’s why we must send the info hash as part of the request to the tracker, we’re saying we want the list of peers that can share this exact torrent.

3.3.3.2 Torrent Size

When we were building the announce request we saw that we needed to fill out the “left” field. Actually we just send the whole size of the torrent files. Let’s see how we can calculate that.

torrent-parser.js:

// rest of file has been left out to save space

const bignum = require('bignum');

module.exports.size = torrent => {

const size = torrent.info.files ?

torrent.info.files.map(file => file.length).reduce((a, b) => a + b) :

torrent.info.length;

return bignum.toBuffer(size, {size: 8});

};github commit #6: add infoHash and size functions to torrent-parser

There are two cases we have to consider - torrents that have one file or more

than one file. If the torrent only has one file then we can get it’s size in

the torrent.info.length property. But if it has multiple files, it will have

a torrent.info.files property instead which is an array of objects for each

file. We have to iterate over these file objects and sum their length property.

There’s one more problem we have to consider with the file size, which is that it may be larger than a 32-bit integer. The easiest way to deal with this is to install a module to handle larger number for us. I’ve decided to use the ‘bignum’ library which is a popular one for this use case. Install it with the command:

npm install –save bignum

You can see that I write the number into a buffer using the bignum.toBuffer

function. The option {size: 8} tells the function you want to write the

number to a buffer of size 8 bytes. This is also the buffer size required by

the announce request.

3.3.4 Finishing touches, response type and retries

Now almost all the pieces have come together for communicating with the

tracker. The last thing we have to do is write the respType function to

identify whether a response was a connect response or an announce response.

There’s more than one way to write this method. After looking at the structure of the two response types I noticed that the connect response has an action value of 0 and the announce response has an action value of 1.

tracker.js:

// rest of file has been left out to save space

function respType(resp) {

const action = resp.readUInt32BE(0);

if (action === 0) return 'connect';

if (action === 1) return 'announce';

}github commit #7: add respType function to tracker.js

And that’s all we need to be able to run the program and get a list of peers for our torrent.

It’s possible that when you run the program it will hang. As I mentioned before it’s possible for udp messages to get dropped in transit, so if that happens just try rerunning the program. Or you could write your own function to retry after a timeout as a bonus exercise!

If you do attempt this, you should wait 2^n * 15 seconds between each request up to 8 requests total according to the BEP. This is called exponential backoff and the reason you want to do this is to balance two concerns.

-

It’s possible your message was lost in transmission, in which case you retransmit as soon as possible.

-

The message is still coming, but the network is experiencing traffic. In this case you don’t want to spam the network with even more requests.

This is a common technique for unreliable network communications.

4. Downloading from peers

Now that we’re able to get a list of peers for our files, we want to actually download the files from them. Here’s a basic overview of how this will work:

-

First you’ll want to create a tcp connection with all the peers in your list.The more peers you can get connected to the faster you can download your files.

-

After exchanging some messages with the peer as setup, you should start requesting pieces of the files you want. As we’ll see shortly, a torrent’s shared files are broken up into pieces so that you can download different parts of the files from different peers simultaneously.

-

Most likely there will be more pieces than peers, so once we’re done receiving a piece from a peer we’ll want to request the next piece we need from them. Ideally you want all the connections to be requesting different and new pieces so you’ll need to keep track of which pieces you already have and which ones you still need.

-

Finally, when you receive the pieces they’ll be stored in memory so you’ll need to write the data to your hard disk. Hopefully at this point you’ll be done!

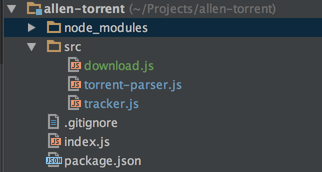

4.1 Setup

Before we start I want to add a new file called download.js. Also, because we’re starting to have more files, I want to create a new folder called “src” and move our code there. Finally I’ve decided to remove the puppy.torrent file. Since it doesn’t have many peers, it’s not going to be that useful for this part of the project. I recommend that you find a small torrent with a lot of peers that you can play around with. Our new file structure should look like this:

I’ve also updated index.js to reflect these changes:

index.js:

'use strict';

const download = require('./src/download');

const torrentParser = require('./src/torrent-parser');

const torrent = torrentParser.open(process.argv[2]);

download(torrent);Note the updated require paths. process.argv[2] will get arguments from

the command line so you can run in the terminal something like:

node index.js /file/path/to/name-of-torrent.torrent

Also note I’m using the method exported by download.js.

github commit #8: restructure and add download.js

4.2 TCP connect to peers

Using tcp to send messages is similar to udp which we used before. In this case we use the “net” module instead of the “dgram” module. Let’s look at an example of how that would work.

const net = require('net');

const Buffer = require('buffer').Buffer;

const socket = new net.Socket();

socket.on('error', console.log);

socket.connect(port, ip, function() {

socket.write(Buffer.from('hello world'));

});

socket.on('data', responseBuffer => {

// do something here with response buffer

});You can see the tcp interface is very similar to using udp, but you have to

call the connect method to create a connection before sending any messages.

Also it’s possible for the connection to fail, in which case we don’t want the

program to crash so we catch the error with socket.on('error', console.log).

This will log the error to console instead. Udp didn’t have this problem

because udp doesn’t need to create a connection.

Applying what we learned above about tcp, we can start writing our download.js file.

download.js:

'use strict';

const net = require('net');

const Buffer = require('buffer').Buffer;

const tracker = require('./tracker');

module.exports = torrent => {

tracker.getPeers(torrent, peers => {

peers.forEach(download);

});

};

function download(peer) {

const socket = net.Socket();

socket.on('error', console.log);

socket.connect(peer.port, peer.ip, () => {

// socket.write(...) write a message here

});

socket.on('data', data => {

// handle response here

});

}We use our getPeers method from the tracker.js file, and then for each peer

we create a tcp connection and start exchanging messages. Before we can go on

we need to know what messages we’ll be sending and receiving.

4.3 Protocol overview

Once a tcp connection is established the messages you send and receive have to follow the following protocol.

-

The first thing you want to do is let your peer know know which files you are interested in downloading from them, as well as some identifying info. If the peer doesn’t have the files you want they will close the connection, but if they do have the files they should send back a similar message as confirmation. This is called the “handshake”.

-

The most likely thing that will happen next is that the peer will let you know what pieces they have. This happens through the “have” and “bitfield” messages. Each “have” message contains a piece index as its payload. This means you will receive multiple have messages, one for each piece that your peer has.

The bitfield message serves a similar purpose, but does it in a different way. The bitfield message can tell you all the pieces that the peer has in just one message. It does this by sending a string of bits, one for each piece in the file. The index of each bit is the same as the piece index, and if they have that piece it will be set to 1, if not it will be set to 0. For example if you receive a bitfield that starts with 011001… that means they have the pieces at index 1, 2, and 5, but not the pieces at index 0, 3,and 4.

It’s possible to receive both “have” messages and a bitfield message, if which case you should combine them to get the full list of pieces.

-

Actually it’s possible to recieve another kind of message, the peer might decide they don’t want to share with you! That’s what the choke, unchoke, interested, and not interested messages are for. If you are choked, that means the peer does not want to share with you, if you are unchoked then the peer is willing to share. On the other hand, interested means you want what your peer has, whereas not interested means you don’t want what they have.

You always start out choked and not interested. So the first message you send should be the interested message. Then hopefully they will send you an unchoke message and you can move to the next step. If you receive a choke message message instead you can just let the connection drop.

-

At this point you’re ready start requesting. You can do this by sending “request” messages, which contains the index of the piece that you want (more details on this in the next section).

-

Finally you will receive a piece message, which will contain the bytes of data that you requested.

4.4 Message types

According to the spec the handshake message should be a buffer that looks like this:

handshake: <pstrlen><pstr><reserved><info_hash><peer_id>

pstrlen: string length of <pstr>, as a single raw byte

pstr: string identifier of the protocol

reserved: eight (8) reserved bytes. All current implementations use all zeroes.

peer_id: 20-byte string used as a unique ID for the client.

In version 1.0 of the BitTorrent protocol, pstrlen = 19, and pstr = "BitTorrent protocol".

Once the handshake has been established there are 10 different types of messages that can be exchanged, all following the same format:

- 4 bytes indicating the length of the message (excluding these 4 bytes)

- 1 byte for the id message

- the rest of the buffer is the message payload which varies by message

I’ll discuss these in more detail as they come up, but you can also find more info in the specs.

I’ve created a new file called message.js with some convenient functions to help build these message buffers.

message.js:

'use strict';

const Buffer = require('buffer').Buffer;

const torrentParser = require('./torrent-parser');

module.exports.buildHandshake = torrent => {

const buf = Buffer.alloc(68);

// pstrlen

buf.writeUInt8(19, 0);

// pstr

buf.write('BitTorrent protocol', 1);

// reserved

buf.writeUInt32BE(0, 20);

buf.writeUInt32BE(0, 24);

// info hash

torrentParser.infoHash(torrent).copy(buf, 28);

// peer id

buf.write(util.genId());

return buf;

};

module.exports.buildKeepAlive = () => Buffer.alloc(4);

module.exports.buildChoke = () => {

const buf = Buffer.alloc(5);

// length

buf.writeUInt32BE(1, 0);

// id

buf.writeUInt8(0, 4);

return buf;

};

module.exports.buildUnchoke = () => {

const buf = Buffer.alloc(5);

// length

buf.writeUInt32BE(1, 0);

// id

buf.writeUInt8(1, 4);

return buf;

};

module.exports.buildInterested = () => {

const buf = Buffer.alloc(5);

// length

buf.writeUInt32BE(1, 0);

// id

buf.writeUInt8(2, 4);

return buf;

};

module.exports.buildUninterested = () => {

const buf = Buffer.alloc(5);

// length

buf.writeUInt32BE(1, 0);

// id

buf.writeUInt8(3, 4);

return buf;

};

module.exports.buildHave = payload => {

const buf = Buffer.alloc(9);

// length

buf.writeUInt32BE(5, 0);

// id

buf.writeUInt8(4, 4);

// piece index

buf.writeUInt32BE(payload, 5);

return buf;

};

module.exports.buildBitfield = bitfield => {

const buf = Buffer.alloc(14);

// length

buf.writeUInt32BE(payload.length + 1, 0);

// id

buf.writeUInt8(5, 4);

// bitfield

bitfield.copy(buf, 5);

return buf;

};

module.exports.buildRequest = payload => {

const buf = Buffer.alloc(17);

// length

buf.writeUInt32BE(13, 0);

// id

buf.writeUInt8(6, 4);

// piece index

buf.writeUInt32BE(payload.index, 5);

// begin

buf.writeUInt32BE(payload.begin, 9);

// length

buf.writeUInt32BE(payload.length, 13);

return buf;

};

module.exports.buildPiece = payload => {

const buf = Buffer.alloc(payload.block.length + 13);

// length

buf.writeUInt32BE(payload.block.length + 9, 0);

// id

buf.writeUInt8(7, 4);

// piece index

buf.writeUInt32BE(payload.index, 5);

// begin

buf.writeUInt32BE(payload.begin, 9);

// block

payload.block.copy(buf, 13);

return buf;

};

module.exports.buildCancel = payload => {

const buf = Buffer.alloc(17);

// length

buf.writeUInt32BE(13, 0);

// id

buf.writeUInt8(8, 4);

// piece index

buf.writeUInt32BE(payload.index, 5);

// begin

buf.writeUInt32BE(payload.begin, 9);

// length

buf.writeUInt32BE(payload.length, 13);

return buf;

};

module.exports.buildPort = payload => {

const buf = Buffer.alloc(7);

// length

buf.writeUInt32BE(3, 0);

// id

buf.writeUInt8(9, 4);

// listen-port

buf.writeUInt16BE(payload, 5);

return buf;

};These functions are mostly straightforward, just pass a payload and then return a buffer with the appropriate length and id. Everything follows directly from the specs mentioned earlier.

github commit #9: add message.js

4.5 Grouping messages

Before going on to actually exchanging messages, there’s one more thing I need to address about tcp. You may have assumed that every time you recieve a data though a socket, it will be a single whole message. But this is not the case. Remember our code for receiving data looked like this:

socket.on('data', receivedBuffer => {

// do stuff with receivedBuffer here

})'

The problem is that the callback gets passed data as it becomes available and there’s no way to know how that data will be broken up. The socket might recieve only part of one message, or it might receive multiple messages at once. This is why every message starts with its length, to help you find the start and end of each message.

Things would be much easier for us if each time the callback was called it

would get passed a single whole message, so I want to write a function

onWhileMsg that will do just that for us.

Like this:

download.js:

function download(peer) {

const socket = net.Socket();

socket.connect(peer.port, peer.ip, () => {

// socket.write(...) write a message here

});

onWholeMsg(socket, data => {

// handle response here

});

}Here is the implementation of onWholeMsg:

download.js:

function onWholeMsg(socket, callback) {

let savedBuf = Buffer.alloc(0);

let handshake = true;

socket.on('data', recvBuf => {

// msgLen calculates the length of a whole message

const msgLen = () => handshake ? savedBuf.readUInt8(0) + 49 : savedBuf.readInt32BE(0) + 4;

savedBuf = Buffer.concat([savedBuf, recvBuf]);

while (savedBuf.length >= 4 && savedBuf.length >= msgLen()) {

callback(savedBuf.slice(0, msgLen()));

savedBuf = savedBuf.slice(msgLen());

handshake = false;

}

});

}How does this function work? First notice the distinction between the function

onWholeMsg, the callback passed to onWholeMsg, and the anonymous callback

passed to socket.on. Next, the key to making this work is to use a closure.

Because the socket.on callback is inside of the onWholeMsg function, the

former will always be able to access the variables of the latter.

So every time the socket recieves data, the socket.on callback is called. It

concats the new data with savedBuf and as long as savedBuf is long enough

to contain at least one whole message, it will pass it to the onWholeMsg

callback and then update savedBuf by slicing out those messages. Basically

savedBuf saves the pieces of incomplete messages between rounds of receiving

data from the socket.

I also have the handshake variable in the closure. This is because the

handshake message doesn’t tell you its length as part of the message. The only

way you can tell you’re receiving a handshake message is that it’s always the

first message you’ll receive. That’s why I start with handshake set to true,

and then the first time we receive a whole message I set it to false.

That all might have been a bit mind-bending if you’re not too familiar with

closures yet, but I encourage you to stick with it and read through the code

carefully. One thing that might help is to realize that the onWholeMsg

function is only getting called once, so the savedBuf and handshake

variables are only initialized once. But then the socket.on callback gets

called multiple times, each time getting and setting the same two variables.

github commit #10: add onWholeMsg function

4.6 Handshake

Now let’s code the handshake:

download.js:

// some code has been left out to save space

const net = require('net');

const tracker = require('./tracker');

const message = require('./message');

module.exports = torrent => {

tracker.getPeers(torrent, peers => {

// 1

peers.forEach(peer => download(peer, torrent));

});

};

function download(peer, torrent) {

const socket = new net.Socket();

socket.on('error', console.log);

socket.connect(peer.port, peer.ip, () => {

// 1

socket.write(message.buildHandshake(torrent));

});

// 2

onWholeMsg(socket, msg => msgHandler(msg, socket));

}

// 2

function msgHandler(msg, socket) {

if (isHandshake(msg)) socket.write(message.buildInterested());

}

// 3

function isHandshake(msg) {

return msg.length === msg.readUInt8(0) + 49 &&

msg.toString('utf8', 1) === 'BitTorrent protocol';

}-

We use the

buildHandshakefunction we created in the message.js file, but this method requires the torrent object, so we now pass that in through thedownloadfunction. -

I didn’t want a long callback function in the

downloadfunction so I created a new function calledmsgHandler. This function will check what kind of message we are receiving and handle it accordingly. Here it checks if the message is a handshake response, and if so it sends the interested message and hopefully the peer will send an unchoke message. -

This function checks if the message is a handshake. Basically just checks that it’s the same length as a handshake and has pstr ‘BitTorrent protocol’.

github commit #11: add handshake handler

4.7 Pieces

After you establish the handshake your peers should tell you which pieces they have. Let’s take a moment to understand what pieces are exactly.

If you open up a torrent file, we saw that it contains data with various properties like the “announce” and “info” properties. Another property is the “piece length” property. This tells you how long a piece is in bytes. Let’s say hypothetically that you have a piece length of 1000 bytes. Then if the total size of the file(s) is 12000 bytes, that means the file should have 12 pieces. Note that the last piece might not be the full 1000 bytes. If the file were 12001 bytes large, then it would be a total of 13 pieces, where the last piece is just 1 byte large.

These pieces are indexed starting at 0, and this is how we know which piece it is that we are sending or receiving. For example, you might request the piece at index 0, that means from our previous example we want the first 1000 bytes of the file. If we ask for the piece at index 1, we want the second 1000 bytes and so on.

4.8 Handling messages

Now I want to start handling messages that aren’t the handshake message. Since these messages have a set format, I can just check their id to figure out what message it is. In order to help me do this I wrote added a function to message.js for parsing message buffers into their parts:

message.js:

// some code has been left out to save space

module.exports.parse = msg => {

const id = msg.length > 4 ? msg.readInt8(4) : null;

let payload = msg.length > 5 ? msg.slice(5) : null;

if (id === 6 || id === 7 || id === 8) {

const rest = payload.slice(8);

payload = {

index: payload.readInt32BE(0),

begin: payload.readInt32BE(4)

};

payload[id === 7 ? 'block' : 'length'] = rest;

}

return {

size : msg.readInt32BE(0),

id : id,

payload : payload

}

};If the message length isn’t greater than 4, then we know it is the keep-ahead message which has no id. If the length isn’t greater than 5 we know that it has no payload. If the id is 6, 7, 8, those messages split the pay load into index, begin, and block/length.

Now we can do this:

download.js:

// some code has been left out to save space

function msgHandler(msg, socket) {

if (isHandshake(msg)) {

socket.write(message.buildInterested());

} else {

const m = message.parse(msg);

if (m.id === 0) chokeHandler();

if (m.id === 1) unchokeHandler();

if (m.id === 4) haveHandler(m.payload);

if (m.id === 5) bitfieldHandler(m.payload);

if (m.id === 7) pieceHandler(m.payload);

}

}

function chokeHandler() { ... }

function unchokeHandler() { ... }

function haveHandler(payload) { ... }

function bitfieldHandler(payload) { ... }

function pieceHandler(payload) { ... }github commit #12: add non-handshake message handlers

So the msgHandler function receives a message, checks the id, and then passes

the payload, if any, to the appropriate handler function. You’ll notice we

aren’t handling all types of messages. The other messages are for sending files

rather than receiving them, so these are the messages I’ll focus on for now.

4.9 Managing connections and pieces

This is a critical point in the project because managing the connections and pieces involves a lot of interesting decisions and tradeoffs. So far we’ve mostly been following the specs directly, but from now on there are many possible solutions and I’ll be going through just one. That’s why I recommend taking some time to consider how you would implement these message handlers yourself before continuing.

Of course a big concern is efficiency. We want our downloads to finish as soon as possible. The tricky part about this is that not all peers will have all parts. Also not all peers can upload at the same rate. On top of that, it’s possible for connections to drop at any time, so we need a way of dealing with failed requests. How can we distribute the work of sharing the right pieces among all peers in order to have the fastest download speeds?

4.9.1 List of requested pieces

After some thought I decided on the following solution. First I would have a single list of all pieces that have already been requested that would get passed to each socket connection. Like this:

download.js:

// some code has been left out to save space

module.exports = torrent => {

const requested = [];

tracker.getPeers(torrent, peers => {

peers.forEach(peer => download(peer, torrent, requested));

});

};

function download(peer, torrent, requested) {

// ...

onWholeMsg(socket, msg => msgHandler(msg, socket, requested));

}

function msgHandler(msg, socket, requested) {

// ...

if (m.id === 4) haveHandler(m.payload, socket, requested);

}

function haveHandler(payload, socket, requested) {

// ...

const pieceIndex = payload.readUInt32BE(0);

if (!requested[pieceIndex]) {

socket.write(message.buildRequest(...));

}

requested[pieceIndex] = true;

}The actual implementation of haveHandler will be more detailed than this, but

you can see how the requested list will get passed through and how it will be

used to determine whether or not a piece should be requested. You can also see

that there is just a single list that is shared by all connections. Some of you

may think that it’s inconvenient to have to pass the requested list to so many

functions. Again, there’s more than one possible solution, so I encourage you

to try you own.

This doesn’t yet account for failed requests, but I’ll be addressing that in a later section.

4.9.2 Job queue

Next I want to create a list per connection. This list will contain all the pieces that a single peer has. Why do we have to maintain this list? Why not just make a request for a piece as soon as we receive a “have” or “bitfield” message? The problem is that we would probaby end up requesting all the pieces from the very first peer we connect to and then since we don’t want to double request the same piece, none of the other peers would have pieces left to request.

Even if it’s possible to use a round-robin strategy so that each peer only gets a second piece to request after all peers have gotten at least one piece to request, there is still a problem. This strategy would lead to all peers having the same number of requests, but some peers will inevitably upload faster than others. Ideally we want the fastest peers to get more requests, rather than have multiple requests bottlenecked by the slowest peer.

A natural solution is to request just one or a few pieces from a peer at a time, and only make the next request after receiving a response. This way the faster peers will send their responses faster, “coming back” for more requests more frequently.

However, because we recieve the “have” and “bitfield” messages all at once, this means we’ll have to store the list of pieces that the peer has. This is so that we can wait until the piece’s response come back, then we can reference the list to see what to request next.

I refer to this as a job queue, because you can think of it like this: each connection has a list of pieces to request. They look at the first item on the list, and check if it’s in the list of already requested pieces or not. If not, they request the piece and wait for a response. Otherwise they discard the item and move on to the next one. When they receive a response, they move on to the next item on the list and repeat the process until the list is empty.

This list will also need to passed through to the handler functions, but it should be created per connection. Like this:

download.js:

// some code has been left out to save space

module.exports = torrent => {

const requested = [];

tracker.getPeers(torrent, peers => {

peers.forEach(peer => download(peer, torrent, requested));

});

};

function download(peer, torrent, requested) {

// ...

const queue = [];

onWholeMsg(socket, msg => msgHandler(msg, socket, requested, queue));

}

function msgHandler(msg, socket, requested, queue) {

// ...

if (m.id === 4) haveHandler(m.payload, socket, requested, queue);

if (m.id === 7) pieceHandler(m.payload, socket, requested, queue);

}

function haveHandler(payload, socket, requested, queue) {

// ...

const pieceIndex = payload.readUInt32BE(0);

queue.push(pieceIndex);

if (queue.length === 1) {

requestPiece(socket, requested, queue);

}

}

function pieceHandler(payload, socket, requested, queue) {

// ...

queue.shift();

requestPiece(socket, requested, queue);

}

function requestPiece(socket, requested, queue) {

if (requested[queue[0]]) {

queue.shift();

} else {

// this is pseudo-code, as buildRequest actually takes slightly more

// complex arguments

socket.write(message.buildRequest(pieceIndex));

}

}So we only request a piece on a “have” if the queue was previously empty

(should be similar for bitfieldHandler). From that point on we only request

pieces once we’ve received a piece response (in pieceHandler). When we

receive a piece we can shift it out of the queue. If the piece has already been

requested, we again shift it out of the queue. You can see that happen in the

requestPiece function which created since it is code shared by both handlers.

4.9.3 Request Failures

The last thing I want to go over before fully implementing the handler

functions is request failures. Right now we are adding the piece index to the

requested array whenever we send a request. This way we know which pieces

have already been requested and then we can avoid the next peer from requesting

a duplicate piece.

However, it’s possible for us to request a piece but never receive it. This is

because a connection can drop at any time for whatever reason. Since we avoid

requesting pieces that have been added to the requested array, these pieces

will never be received.

You might think we could just add pieces to the list when we receive them. But then between the time that the piece requested and received any other peer could also request that piece resulting in duplicate requests.

I’ve found that the easiest solution is to maintain two lists, one for

requested pieces and one for received pieces. We update the requested list at

request time, and the received list at receive time. Then whenever we have

requested all pieces but there are still pieces that we haven’t received, we

copy the received list into the requested list, and that will allow us to

rerequest those missing pieces.

However, it’s inconvenient to have to maintain multiple lists when just one data abstraction should be necessary. So I’ve create a new file called Pieces.js:

Pieces.js:

'use strict';

module.exports = class {

constructor(size) {

this.requested = new Array(size).fill(false);

this.received = new Array(size).fill(false);

}

addRequested(pieceIndex) {

this.requested[pieceIndex] = true;

}

addReceived(pieceIndex) {

this.received[pieceIndex] = true;

}

needed(pieceIndex) {

if (this.requested.every(i => i === true)) {

// use slice method to return a copy of an array

this.requested = this.received.slice();

}

return !this.requested[pieceIndex];

}

isDone() {

return this.received.every(i => i === true);

}

};You can see that we need to initialize the Pieces instance with the total number of pieces, otherwise it’s not possible to know when we’re finished getting all the pieces. We assume that the array index is the same as the piece index, and then we set that index to true if it has been requested/received (all indexes start as false by default). This is a nice way to look up a piece’s status without iterating through the arrays.

This object can now be used to replace the requested array from earlier.

4.10 Implementing the message handlers

4.10.1 Choke and unchoke

Dealing with choke and unchoke states is a little bit tricky because we don’t

want to request any pieces until we’ve been unchoked. I think the simplest way

to enforce this is to create a new object that holds both our queue array as

well as a choked property.

Now we can add this new object and write out the choke and unchoke handlers.

download.js:

'use strict';

const net = require('net');

const tracker = require('./tracker');

const message = require('./message');

// 1

const Pieces = require('./Pieces');

module.exports = torrent => {

tracker.getPeers(torrent, peers => {

// 1

const pieces = new Pieces(torrent.info.pieces.length / 20);

peers.forEach(peer => download(peer, torrent, pieces));

});

};

// 1

function download(peer, torrent, pieces) {

const socket = new net.Socket();

socket.on('error', console.log);

socket.connect(peer.port, peer.ip, () => {

socket.write(message.buildHandshake(torrent));

});

// 1

const queue = {choked: true, queue: []};

onWholeMsg(socket, msg => msgHandler(msg, socket, pieces, queue));

}

function onWholeMsg(socket, callback) {

let savedBuf = Buffer.alloc(0);

let handshake = true;

socket.on('data', recvBuf => {

// msgLen calculates the length of a whole message

const msgLen = () => handshake ? savedBuf.readUInt8(0) + 49 : savedBuf.readInt32BE(0) + 4;

savedBuf = Buffer.concat([savedBuf, recvBuf]);

while (savedBuf.length >= 4 && savedBuf.length >= msgLen()) {

callback(savedBuf.slice(0, msgLen()));

savedBuf = savedBuf.slice(msgLen());

handshake = false;

}

});

}

// 1

function msgHandler(msg, socket, pieces, queue) {

if (isHandshake(msg)) {

socket.write(message.buildInterested());

} else {

const m = message.parse(msg);

if (m.id === 0) chokeHandler(socket);

// 1

if (m.id === 1) unchokeHandler(socket, pieces, queue);

if (m.id === 4) haveHandler(m.payload);

if (m.id === 5) bitfieldHandler(m.payload);

if (m.id === 7) pieceHandler(m.payload);

}

}

function isHandshake(msg) {

return msg.length === msg.readUInt8(0) + 49 &&

msg.toString('utf8', 1) === 'BitTorrent protocol';

}

function chokeHandler(socket) {

socket.end();

}

// 1

function unchokeHandler(socket, pieces, queue) {

queue.choked = false;

// 2

requestPiece(socket, pieces, queue);

}

function haveHandler() {

// ...

}

function bitfieldHandler() {

// ...

}

function pieceHandler() {

// ...

}

//1

function requestPiece(socket, pieces, queue) {

//2

if (queue.choked) return null;

while (queue.queue.length) {

const pieceIndex = queue.shift();

if (pieces.needed(pieceIndex)) {

// need to fix this

socket.write(message.buildRequest(pieceIndex));

pieces.addRequested(pieceIndex);

break;

}

}

}github commit #14: add choke and unchoke handlers

Here’s the new download.js file in its entirety since there’s quite a bit going on here. Fortunately most of it was covered in the previous sections. Most of these changes are simply passing our two new data structures Pieces and queue object through through to the handlers. I’ve marked all these lines with a 1.

In the previous section I changed the Pieces class so that its constructor

takes the total number of pieces as an argument. You can find this value by

looking up the torrent.info.pieces.length property and dividing by 20. The

torrent.info.pieces is a buffer that contains 20-byte SHA-1 hash of each

piece, and the length gives you the total number of bytes in the buffer.That’s

why we divide by 20 to get the total number of pieces.

The other big change is that we begin requesting pieces when we are unchoked

(which I’ve marked with 2). You can see that when you’re choked, you can’t make

any requests, and nothing happens. If you’re unchoked then we shift out piece

indexes until we find one that we don’t already have using the pieces.needed

method we coded earlier and request that piece. Finally we add the requested

index into pieces and break the loop. The next request won’t happen until we

get a “piece response” which we’ll code up in the pieceHandler function.

You might have noticed that I wrote a comment above socket.write(message.buildRequest(pieceIndex));

that something needs to be fixed. We’ll address this problem in the next

section.

4.10.2 Pieces vs. blocks

The function message.buildRequest in the above code needs to take an object

with an index, begin, and a length property. These are the required fields for

the payload of a request message.

But what are these fields for exactly? Well index is easy, it’s the piece index

that is currently being passed in. What about begin and length?

These two properties are necessary because sometimes a piece is too big for one message. Although there is some dispute about the best size, it is typically considered to be around 2^14 (16384) bytes. This is called a “block”, where a piece consists of one or more blocks. If the piece length is greater than the length of single block, then it should be broken up into blocks with one message sent for each block.

So the “begin” field is the zero-based byte offset starting from the beginning of the piece, and the “length” is the length of the requested block. This is always going to be 2^14, except possibly the last block which might be less.

We’re going to need a number of modifications to accomodate this. But first I want to write some function in torrentParser.js that will help me determine the piece and block lengths for a given piece index.

torrent-parser.js:

// some code left out to save space

const bignum = require('bignum');

module.exports.BLOCK_LEN = Math.pow(2, 14);

module.exports.pieceLen = (torrent, pieceIndex) => {

const totalLength = bignum.fromBuffer(this.size(torrent)).toNumber();

const pieceLength = torrent.info['piece length'];

const lastPieceLength = totalLength % pieceLength;

const lastPieceIndex = Math.floor(totalLength / pieceLength);

return lastPieceIndex === pieceIndex ? lastPieceLength : pieceLength;

};

module.exports.blocksPerPiece = (torrent, pieceIndex) => {

const pieceLength = this.pieceLen(torrent, pieceIndex);

return Math.ceil(pieceLength / this.BLOCK_LEN);

};

module.exports.blockLen = (torrent, pieceIndex, blockIndex) => {

const pieceLength = this.pieceLen(torrent, pieceIndex);

const lastPieceLength = pieceLength % this.BLOCK_LEN;

const lastPieceIndex = Math.floor(pieceLength / this.BLOCK_LEN);

return blockIndex === lastPieceIndex ? lastPieceLength : this.BLOCK_LEN;

};In pieceLen I had to use the bignum library to deal with the totalLength

variable because it’s in an 8 byte buffer. pieceLen and blockLen are

similar, they just return the piece length or block length, respectively,

unless they happen to be the very last piece or block. Then it might be shorter

than a full piece or block. Piece length can be found in the torrent file, and

block length is 2^14 bytes by convention.

Also, both the queue object and the Pieces class should be changed to deal with blocks instead of just pieces. For the queue object we just used a plain javascript object with two properties, but with the added complexity of dealing with blocks, I’ve decided to create a new Queue class.

Queue.js:

'use strict';

const tp = require('./torrent-parser');

module.exports = class {

constructor(torrent) {

this._torrent = torrent;

this._queue = [];

this.choked = true;

}

queue(pieceIndex) {

const nBlocks = tp.blocksPerPiece(this._torrent, pieceIndex);

for (let i = 0; i < nBlocks; i++) {

const pieceBlock = {

index: pieceIndex,

begin: i * tp.BLOCK_LEN,

length: this.blockLen(this._torrent, pieceIndex, i)

};

this._queue.push(pieceBlock);

}

}

deque() { return this._queue.shift(); }

peek() { return this._queue[0]; }

length() { return this._queue.length; }

};Now the queue is a list of pieceBlock objects. I admit the terminology is getting

a little confusing but I’m referring to the object built in the queue method

that have index, begin, and length properties. These pieceBlock objects have the

same structure as the payload when we send a request message (check the

buildRequest function in message.js), so we can pass them to the request

builder directly.

More generally, from now on we want to deal with these objects instead of the piece index, because it also gives us information about the block. Here’s an outline of when/where we would use these objects:

-

When we receive a “have” message, we get a piece index, but we fill the queue with these piece objects, one for each block for each piece.

-

When we deque an object we can pass it to the request builder and make a request for the associated block.

-

The Pieces class that tracks requested and received pieces should be able to add a

pieceBlock. We’ll see this implemented next.

Note that the constructor need to get passed a torrent object now, instead of just the number of pieces.

I’ve prepended private variables with an underscore, and the other methods just

give us public methods to interact with the private _queue variable. I’ve

left the choked without an underscore to indicate it is a public property. If

you’re not familiar with private and public properties, it’s not that

important. The idea is that users of this module shouldn’t use the underscore

prepended properties.

Here is the Pieces class altered to handle blocks.

Pieces.js

'use strict';

const tp = require('./torrent-parser');

module.exports = class {

constructor(torrent) {

function buildPiecesArray() {

const nPieces = torrent.info.pieces.length / 20;

const arr = new Array(nPieces).fill(null);

return arr.map((_, i) => new Array(tp.blocksPerPiece(torrent, i)).fill(false));

}

this._requested = buildPiecesArray();

this._received = buildPiecesArray();

}

addRequested(pieceBlock) {

const blockIndex = pieceBlock.begin / tp.BLOCK_LEN;

this._requested[pieceBlock.index][blockIndex] = true;

}

addReceived(pieceBlock) {

const blockIndex = pieceBlock.begin / tp.BLOCK_LEN;

this._received[pieceBlock.index][blockIndex] = true;

}

needed(pieceBlock) {

if (this._requested.every(blocks => blocks.every(i => i))) {

this._requested = this._received.map(blocks => blocks.slice());

}

const blockIndex = pieceBlock.begin / tp.BLOCK_LEN;

return !this._requested[pieceBlock.index][blockIndex];

}

isDone() {

return this._received.every(blocks => blocks.every(i => i));

}

};Now the requested and received arrays, which used to hold the status of a

piece index, now holds an array of arrays, where the inner arrays hold the

status of a block at a give piece index. So if you wanted to find out the

status of a block at index 1 for a piece at index 7, you could look up

_requested[7][1] and check if it’s set to true. As before all values are

initially set to false.

Also note that these methods expect to be passed a pieceBlock, the same ones we

saw in the Queue class. This means when we peek a pieceBlock from a queue and

request it, or deque a pieceBlock when we’ve received it, we can pass the

pieceBlock directly to addRequested or addReceived respectively.

Finally there’s a few changes that need to be made in download.js where we use the Queue and Pieces classes.

download.js:

// some code has been left out to save space

const Queue = require('./Queue');

module.exports = torrent => {

tracker.getPeers(torrent, peers => {

// need to pass torrent now

const pieces = new Pieces(torrent);

peers.forEach(peer => download(peer, torrent, pieces));

});

};

function download(peer, torrent, pieces) {

// ...

// use new Queue class

const queue = new Queue(torrent);

onWholeMsg(socket, msg => msgHandler(msg, socket, pieces, queue));

}

function requestPiece(socket, pieces, queue) {

if (queue.choked) return null;

while (queue.length()) {

const pieceBlock = queue.deque();

if (pieces.needed(pieceBlock)) {

socket.write(message.buildRequest(pieceBlock));

pieces.addRequested(pieceBlock);

break;

}

}

}github commit #15: support blocks

This code is mostly the same as before except that we’re passing and using our new Pieces and Queue classes. Also we now use the pieceBlock object instead of just the piece index.

4.10.3 Have and bitfield

These two messages do roughly the same thing, which is tell us which pieces the peer has for sharing. Let’s start with the “have” message.

download.js:

// some code has been left out to save space

function haveHandler(socket, pieces, queue, payload) {

const pieceIndex = payload.readUInt32BE(0);

const queueEmpty = queue.length === 0;

queue.queue(pieceIndex);

if (queueEmpty) requestPiece(socket, pieces, queue);

}This will add the piece index into the queue. We also want to kick off the piece requesting process if this is the first item added to the queue. Why only the first? Because as we discussed before, we want to wait for the piece response to come back before requesting the next piece.

Now let’s look at bitfieldHandler:

download.js:

// some code has been left out to save space

function bitfieldHandler(socket, pieces, queue, payload) {

const queueEmpty = queue.length === 0;

payload.forEach((byte, i) => {

for (let j = 0; j < 8; j++) {

if (byte % 2) queue.queue(i * 8 + 7 - j);

byte = Math.floor(byte / 2);

}

});

if (queueEmpty) requestPiece(socket, pieces, queue);

}github commit #16: add have and bitfield handlers

The payload here is a buffer, which you can think of as a long string of bits. If the peer has the index-0 piece, then the first bit will be a 1. If not it will be 0. If they have the index-1 piece, then the next bit will be 1, 0 if not. And so on. So we need a way to read individual bits out of the buffer.

I don’t want to dwell on this part too much. I think it’s a good exercise for the reader to try themselves. Basically repeatedly dividing by 2 and taking the remainder will convert a base-10 number to a binary number, giving you the digits of the binary number from least to most signifiant bit (right to left).

Just like haveHandler we queue the piece index, and only make a request we

are adding the first piece in the queue.

4.10.4 Piece response handler

This is the final section before we can start downloading torrents! We just

need to write out the pieceHandler which is for when we receive the actual

bytes of the piece we requested.

The main things we want to do in this function are:

- Add the piece to the list of received pieces.

- Write the bytes to file.

- Request the next needed piece. Or…

- If there are no more pieces to download in the queue we close the socket connection.

download.js:

// some code has been left out to save space

function pieceHandler(socket, pieces, queue, torrent, pieceResp) {

pieces.addReceived(pieceResp);

// write to file here...

if (pieces.isDone()) {

socket.end();

console.log('DONE!');

} else {

requestPiece(socket,pieces, queue);

}

}I’m calling the response piece pieceResp. It’s slightly different from a

pieceBlock because instead of the length the of piece, it contain the actual

data for the piece. But the index and begin properties are the same, so

you can pass it to the pieces.addReceived method normally. We also get to use

our pieces.isDone method here to check if we’re done. If we are we close the

socket, otherwise we request the next piece.

The only thing we need to do now is write the bytes to file. We can do this

using the fs module by using the fs.openSync

method to open a file. This will return a file descriptor, which we pass to the

fs.write

method. Since want all the peers to be writing to the same file, creating the

file descriptor is one of the very first things we need to do:

download.js:

// some code has been left out to save space

module.exports = (torrent, path) => {

tracker.getPeers(torrent, peers => {

const pieces = new Pieces(torrent);

const file = fs.openSync(path, 'w');

peers.forEach(peer => download(peer, torrent, pieces, file));

});

};The openSync method takes a file path (this includes the file name), which is

where the file will be created. Note that this exported function now takes a

second path argument. We then use ‘w’ or write mode to create and write to

a new file. You could also change this code so that you can resume downloads

instead of overwriting and previous existing data, but we’ll keep things simple

for now. This file descriptor should get passed all the way down to the

pieceHandler function.

The final pieceHandler function should look like this:

download.js:

// some code has been left out to save space

function pieceHandler(socket, pieces, queue, torrent, file, pieceResp) {

console.log(pieceResp);

pieces.addReceived(pieceResp);

const offset = pieceResp.index * torrent.info['piece length'] + pieceResp.begin;

fs.write(file, pieceResp.block, 0, pieceResp.block.length, offset, () => {});

if (pieces.isDone()) {

console.log('DONE!');

socket.end();

try { fs.closeSync(file); } catch(e) {}

} else {

requestPiece(socket,pieces, queue);

}

}Since pieceResp.begin only tells us the offset relative to the piece it’s in,

we have to calculate the absolute offset ourselves. Then we just write the

block of data to the file descriptor we create earlier. That’s it!

The very last thing we need to do is pass the filepath into the exported function.

index.js:

'use strict';

const download = require('./src/download');

const torrentParser = require('./src/torrent-parser');

const torrent = torrentParser.open(process.argv[2]);

download(torrent, torrent.info.name);The only change we made here is to pass the torrent file’s name to the

download function.

github commit #17: add piece handler

5. Conclusion